This blog is about “Horrid Mysteries”, an innovative gothic horror one-shot system that we played on the pod. You can check out those episodes here (you might have to scroll down the episode list):

We Swim Below [Part 2] – Dice So Nice I Said Dice Twice

In this post I’m going to talk about why I love it, and suggest some added features for it that could make it, in my opinion, one of the best TTRPGs around.

What is “Horrid Mysteries”?

Horrid Mysteries is a free (PWYW) gothic horror TTRPG by Jacob Marks ( you can get it here). It is geared for one-shots, using a system that visibly draws every player closer and closer to a dramatic ending, and a character and adversary creation system that allows you to get going moments after you decide to play, so long as you’re down to improvise. If improv isn’t your jam, you can create characters and adversaries using the game’s generation system and then go away and write something.

Why do I love it so much?

Jacob Marks’s game is simple, innovative, and bloody fun. Instead of dice, Horrid Mysteries opts for a playing card based system. Whenever your character attempts to do something difficult or important, you draw a card from a shuffled deck. If the card is a face card, you succeed, if not you fail. If the character has some kind of advantage, they need a red card to succeed. In very special circumstances where your character is doing something they would ordinarily be expected to succeed at, but the stakes of them pulling it off are very high, the player needs to draw a number card in order to succeed. Jokers always succeed.

This system is simple to understand, creates a great sense of tension and fun in drawing cards, and preserves that good ol’ RPG randomness. The difficulty system described above means no one card is inherently better than any other (except for jokers, which are always successes). Depending on what the GM has ruled, you might be crossing your fingers hoping for the last king, or for the last 2.

But that’s hardly anything new. Cards have been used in place of dice in many TTRPGs, so why does it work so well here? Well, the deck of cards serves a secondary purpose: pacing and ending the story. When you draw a card, it never goes back into the deck. That means there is a finite number of checks the whole party can attempt (54 to be exact). So what happens when you run out? Your characters lose. The big bad monster gets them. It’s a rule that creates a true sense of tension as you watch that deck of cards dwindle more and more, your characters coming closer and closer to a potentially gruesome end. A perfect way to make a game scary, as every failed check is a wasted card, making you fear to draw. It’s also a perfect way to gear a game to a one-shot. Everybody has a visual indication of how much longer the game might last, and how urgently they need to buck up their ideas if things aren’t going well.

The game uses cards to help you generate genre-appropriate characters and story elements very quickly. You can get going in this game after very little prep. Using cards you can generate a setting, an adversary monster, and characters with unique boons and weaknesses. As is the case in many indie gems, Jacob Marks has borrowed some tables from Ben Milton’s Maze Rats, so you can have a character with a simply fabulous but still appropriate name. For example “Erasmus Vandermeer”.

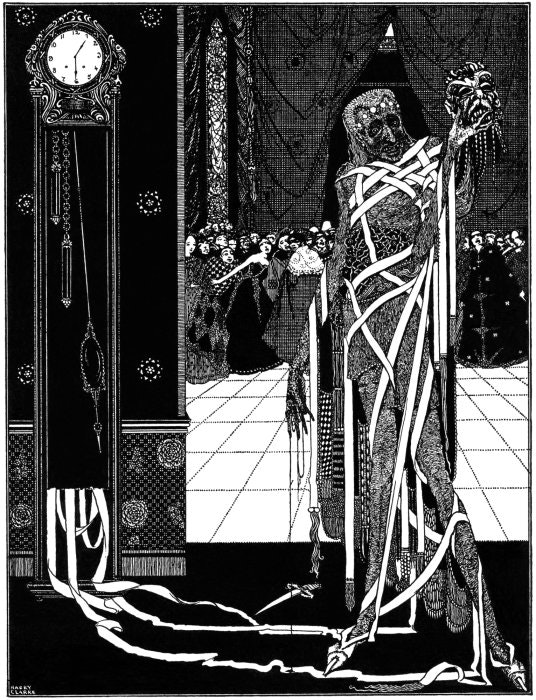

I am also particularly fond of this PDF for introducing me to the art of Harry Clarke, which it uses to set the tone very effectively. It also rocks. Check this out:

Why this horror one-shot game?

If you’re a TTRPG hobbyist (and if you’re reading this, you definitely are. Or you’re my mum. Even then, my mum would have stopped reading by now. If not, hi mum!) you’ve probably got a list of horror one-shot games you intend to play, if only you could find people who wanted to play them with you. Every TTRPG blog and YouTube channel worth its adspace has made a list like “5 Horror one-shot TTRPG games you should try this Halloween!”

On every one of those lists is “Dread” by The Impossible Dream, and for good reason. It’s a really really good game that uses a Jenga tower to resolve its actions. We played it (check it out in the podcast player at the top of the page) and had a whale of a time. It’s a game so good that it’s mentioned in the top rated comment on this reddit post asking for horror games not for one-shots. It’s a game so good I’m going to devote basically an entire section to it in this blog post about a different game.

Before I really get into that though, for comparing this game to every other horror one-shot game in general (like you probably thought I was going to do here), I would simply refer to my thoughts in the above section. It’s a great game with a really great horror-amplifying central system.

Now, the reason I’m presently going to focus on Dread, is because Dread has sort of become the default horror one-shot game, at least in the RPG discourse that I see. It is the DnD of this particular field, but much more deserving of the status. And, because I think there are some interesting comparisons and contrasts to draw between Horrid Mysteries and Dread.

In Dread, every time a character wants to do something that they wouldn’t automatically succeed at, the player must pull a block from the tower. They must commit to the first block they touch. If they back out, realising that block spells doom, their character fails at what they were trying to do. If they knock over the tower, their character dies. Much as Horrid Mysteries does with the ever-dwindling deck of cards, this creates a visual representation of coming doom. It also means it becomes harder and harder for characters to succeed as the tower becomes more and more unstable. This is true in most cases for Horrid Mysteries as well, as the remaining pool of possible cards to pull from becomes ever smaller. However it is worth noting that it is possible to have a deck where the final two cards are jokers, so the final two draws are in fact the “easiest”.

The parallels are clear. Both games use a physical object that becomes less and less functional as time passes as a visual and tactile representation of doom. This feature also polices the length of the game, making it unlikely any one playthrough of either game lasts more than two sessions at most. This is what makes these two games the best in the genre for me. I promise I’m going somewhere with this.

There are two key differences between the games that I would like to focus on:

One: In Dread, when the tower falls, it is only one character that is affected. Whoever knocked over the tower has spelled doom for their character, but the rest of the party plays on. This can create an awkward stretch of the game where one or two players don’t really get to play anymore, but have to sit and watch. The Dread rules do include some options for letting them be ghosts that can’t do anything, but that’s still a bit rubbish as a player. After the tower falls, it is built back up again, usually with a few pieces missing. Thus, the Jenga game becomes a lot easier, removing a lot of the tension that was mounting in a way I find can make the death feel a little anticlimactic. Meanwhile, in Horrid Mysteries, when the deck runs out, that is a loss for the whole party. Everybody is united in their victory or failure, and everybody feels the tension rise together, not just the player of the acting character.

Two: Using cards instead of Jenga is perhaps a truer RPG experience, and definitely a more accessible one. It requires very little for a person to successfully take a card from a deck. This means that the random element of the deck, and the difficulty determined by the GM with regard to the character’s abilities, are the only things that determine success. One of the glories of playing RPGs is that you can be people entirely different from yourself. You can play people with the strength of the hulk, or the intelligence of Einstein, when you obviously possess neither trait in real life. Your real world limitations (and indeed, advantages) are not usually factors in your role-playing, which means that the only real limits of yours being tested are the limits of your imagination. However, this isn’t explicitly the case in Dread. Jenga, is itself, a skill-based game. You can be amazing at Jenga (like me) or rubbish (like everyone who tries to beat me). Which leads to the unfortunate truth that, if you are bad at Jenga, your character is worse at staying alive, for reasons that don’t relate to your role-playing. This can create an inaccessible game for anyone with disabilities that effect their dexterity or depth-perception. People with DCD (Dyspraxia) for example might feel quite disadvantaged. I have close friends with tremors as a result of surgery, and I feel like I can’t really suggest this game to them, despite how fun I know it to be. Players could always pull by proxy for other players, but this does create a space where a disabled player may have to ask for that, or might feel left out in a way that I think they wouldn’t if another player was pulling a card for them. A card deck is also a much easier thing to simulate online than a Jenga tower, which creates more opportunities to actually get your friends to play a game with you.

Now, I’d like to make clear that the purpose of this section is not to assert that you should stop playing Dread and start playing Horrid Mysteries. I love both games, and I think there are merits and workarounds to a lot of the things I’ve singled out above. The player-by-player death of Dread works very well for simulating slasher stories, and I don’t think that lack of remote-play options for a game is necessarily a fair criticism. If a game is designed to be played with a ball, its not really fair to say its less fun if you didn’t use a ball. And while I can talk about the possible advantages of using cards over a Jenga tower, there is a huge advantage of using a Jenga tower, and that is that you get to use a Jenga tower. I love Jenga.

No, the real purpose of this section is to allow you to consider switching it up. I know a lot of people play Dread once a year. If anything I’ve pointed out above appeals to you, give Horrid Mysteries a go!

How could it be better?

I think I’ve made clear I’m a really big fan of Horrid Mysteries, but I don’t think it’s perfect. Like many games, Horrid Mysteries is affected by the blessing and curse of being a short and simple game. I first became aware of it because it was submitted to itch.io’s one-page game jam in 2021. Whether or not Jacob Marks created the game specifically for that jam, I don’t know, but as a one-page game it comes with the universal advantage of being easy to acquire and digest, and the universal drawback of the rules having limited scope.

There is true beauty in short simple games. They’re what allow podcasts like ours to sustain themselves. If Jacob Marks reads the suggestions I’m about to make for expanding the game and considers them all dumb bullshit that only serves to overcomplicate a lovely one-pager, I would consider that entirely valid. So without further ado, my ideas:

Fleshing out character creation + Calamities

Characters, like everything else in Horrid Mysteries, are very simple. They are composed of four things: A name, a useful accoutrement, a boon, and a “calamity”. You can draw cards to generate all of these things, allowing you to get a complete character in a matter of seconds. It is in its speed that this system has its advantages, but when we actually played the game we found ourselves a little bit uncertain on how to actually use these details in play. I’m going to focus on the “Calamity” in particular.

There are thirteen possible “calamities” that can affect your character. You pull a card to determine which one will be relevant to you. How exactly these calamities are supposed to affect gameplay is not explicitly stated in the game’s rules. When we played, we treated them as simple character flaws that the players can use to enhance their roleplaying, but we gave them no mechanical relevance. It would be quite hard to insist anyone be beholden to them, because they are not all made equal. If you draw a Queen during character creation, your calamity is “Coward”, and if you draw a 3, your calamity is “Nightmares”. If you had to roleplay your calamity to the best of your ability, one of these would cause you to run away from the adversary, not engaging with the story at all, and the other would only really affect you if you fell asleep for some reason.

I propose to use these as story-guides and event triggers. During character creation, you still draw a card to determine your calamity. So if you draw a 10 and get “Addict”, you should decide what your character is addicted to and how it affects their life and decisions, as you would normally. However, during gameplay, if anyone draws a 10, your character should suffer from their calamity in some way. In this instance, if someone draws a 10 resulting in a failure, it could be because your character got the shakes at that exact moment, ruining the plan. If someone draws a 10 resulting in a success, you could narrate how your character helps using their laser-focus due to their motivation to get their next hit. Or perhaps they’ve just used whatever substance they’re addicted to to keep them level. This would make drawing cards more exciting, and capitalise on their random nature more. As this is supposed to be a “calamity” that affects your character, you might rule that drawing your calamity card is always a failure, no matter the current difficulty system.

As for the boons and useful accoutrements, they are sensible, if only a little lacking. There are only four* possibilities for each, and including an ace-king draw table of thirteen possibilities, like exists for calamities, might make finishing your character a bit more exciting.

Difficulty, Advantage, and Card Counters

The process of assigning difficulty in Horrid Mysteries is an interesting one. As described above, under most circumstances, you must pull a face card from the pack. If your character’s “boon” is relevant to the action at hand, then you must instead pull any red card, increasing your chances. If the task is something your character would be ordinarily able to do without pulling, but the stakes of pulling it off are significant enough to want to introduce a random element, then you must pull any number card. In all cases, a joker is a success.

There is no inherent issue with this. It is a robust system, however, the difficulty is not a slider, as it is in other TTRPGs. It’s not a number from 5-30 that you move up or down depending on how hard the GM reckons an action is. Instead the easier levels are unlocked by conditions, not by how good your character is at the task at hand, or how difficult you think that task would actually be. According to the rules, you can only move down to the easier difficulty of only pulling red cards if you have a relevant boon. That means there are a lot of tasks, of wildly different difficulties, that a boon might not apply to, that all have the same difficulty.

For example; A character has the boon “Occult Tools”, perhaps you as a group determine that character has some crucifixes and a copy of the necronomicon. Here are two situations where that wouldn’t be of any help:

- The character has been suspended by their ankles by the adversary. They are being slowly lowered into a tank of water. If they aren’t able to free themselves they will drown.

- A cat has stolen something the character needs and has run up a tree. The character must try and coax the cat down from that tree.

Both of these situations would create the same difficulty of card pull, a face card. It is also easy to apply this logic to all three levels of difficulty. Because the card required is determined by circumstances, and not by how hard a thing actually is to do, it means that sometimes the difficulties don’t really makes sense. I have a potential solution, introduce an advantage or disadvantage system.

I suggest sticking with the condition system to determine the target, but determining that things are particularly difficult (perhaps a character has broken their arm), and making the player pull two cards, choosing the less favourable card, and shuffling the other card back into the deck. Similarly, allow players to argue their case that they should be able to pull two cards and pull the more favourable card.

The reason I suggest sticking with the condition system, and not treating the existing difficulty levels like a slider (e.g. “Hey this is really easy actually, you can do any number card instead of any red card”) is because, with only three levels of difficulty, and the game being grisly and full of consequence, the hardest level (face cards) would be the most likely one. That would create a scenario where face cards are more valuable than the other cards, and one of the things I love about the original system, is that no card is inherently better than any other card (except for jokers). I think it is important to try and preserve this quality, as it will make it harder for any card-counters to think things like “there’s no face cards left, we’re doomed, what’s the point.”

Party Size Balancing

This is a minor note, but an important one I think. If you listened to our episodes playing this game, you’ll remember that we finished this game with a lot of cards left over. We didn’t come to a place where things got particularly tense, and I imagine this is because we were a small party. There were only 2 players not including the GM, and this game was likely designed for the more standard 4-6. Experimenting with a formula like “Remove three cards from the deck for every player under 4.” might help limit the cards enough to drive that suspense for smaller groups.

The Endless Potential of This System

Using a slowly depleting deck of cards as a countdown to doom is genius, and could be used in a great many more genres than just gothic horror. Any kind of story where the protagonists are in a race against time could be gamified to great effect using this card system. I’d love to see more games, or expansions to this game that allow these mechanics to be applied to new stories. Here’s some ideas:

Action Movie: Counter Terrorist Operation

Think Die Hard. A group of terrorists have taken over a building. They have hostages, and if the player characters don’t get to the top of the tower in time to stop them, they’ll either start killing hostages, or they’ll escape with the nuclear launch codes, or something. The more cards you pull, the closer the terrorists/bad guys/whatever get to achieving their goal.

Thriller Movie: Trapped on a moving Vehicle

Think Snakes On A Plane, or Alien. The PCs are trapped on a plane, or a train, or a spaceship, and they can’t get off the plane/train/spaceship because it is in the sky/the engine room is locked and its speeding on/it is in space. There is a monster, or a lot of snakes, or an alien on the vehicle with them. As time goes on, the train gets closer to crashing into another train, or the alien gets big and strong enough to kill everyone, or whatever happens in Snakes On A Plane. The players must solve the problem before it’s too late.

Modern Horror: Let’s play a game.

Think Saw. The players are trapped, and only have so long to do a series of macabre challenges. Failure to get out in time will result in death.

So that’s it. Those are far too many of my thoughts on Jacob Marks’s Horrid Mysteries. Which you should go and get right now.

Thanks for reading

xoxo

Carlyle

Leave a comment